Pride and Productivity or Know thy Limits

If you got here from the "problem index" on the everyday systems home page, you may be wondering, "Pride is a problem???"

I know it's hard to swallow in the age of "self-esteem," but yes, pride can be a problem - a big problem, in fact. But don't break out your cilice and scourge just yet, because I'm not talking about pride here as the opposite of self-loathing, I'm talking about it in the sense of hubris, the pride of not knowing your limits and attempting too much. The wonderful irony about this sort of overambitious pride is, that if you really want to accomplish anything, the key is knowing what you can't get done. Humility is the key to productivity -- and to satisfying the good kind of pride (pride has the unique distinction of being both a deadly sin and an Aristotalian virtue -- accurately, in both cases, I think). "Chain of Self-Command" is a way of limiting and focusing your ambition so you can get more done.

Note: most of the content below originally appeared in various episodes of the Everyday Systems Podcast. I'll provide links to the relevant episodes where appropriate, and hope you'll forgive my flagrant and repeated acts of self-plagiarism. I wanted to make sure this previously scattered material was available in one convenient and well-organized place.

Establish a Chain of Self-Command on Three Temporal Scales

Organize your task management on three scales, three temporal scales. It's a hierarchy. On the largest, lifetime scale, you're the general. The commander in chief. You make big vague strategic decisions. Like, "lose weight" or "stop smoking" or "learn German" or "get these big projects done at work." You don't worry about how, you don't even worry too much about whether they should be done. You just make a note, that these are problems that ought to be dealt with somehow at some point, or at least carefully considered. On the first of each month, you change roles, you're an officer. You take the one of the general's big vague ideas and translate it into a specific, concrete monthly goal -- a monthly resolution. Example: start to lose weight by doing the No S Diet. Resolve to do it for a month, and keep track of your compliance with the habitcal. That's a good monthly goal. Every day, you switch roles again. Your daily self is a foot soldier. This is the smallest granularity. You carry out the officer's orders (among other logistical tasks), and succeed or fail. So the general gives direction, the officer interprets that direction, and the soldier implements it. You're an army of one, like that commercial. You in a given year consist of one general, 12 officers, and 365 enlisted men.

What's the point of this analogy? Why is it helpful to think this way? Because if you don't, if you're always general, officer, and soldier at the same time, there's nothing to stop you from immediately countermanding your own orders whenever you feel like it. If you don't make a distinction between your boss self and your obedient self, you never really get the idea that you have to obey your own commands, you're just shouting out orders all the time. You have an army of 365 generals -- an army that is going to get slaughtered. With chain of self-command, you learn to obey yourself. By making these processes distinct, you learn this self-obedience, and yet it doesn't feel oppressive, because you know that a month later, you're in command again, you're an officer, and eventually, you're the general himself. And by obeying, for a month, even when you've made some dumb resolutions, your commanding self learns quickly what works and what doesn't.

You've got to divide your problems and goals somehow, and this is a pretty simple and unambiguous way to do it. Once you've divided up your ambitions like this, it's easy to apply focusing limits. I'll describe how to do this in detail for each of the roles.

Note: listen to (or read) more about the Chain of Self-Command in the podcast episode in which it was originally described.

1. Footsoldier: Daily Planning with Personal Punch Cards

I implement the daily "footsoldier" rank in the chain of self-command with index cards. I call them personal punch cards, like the punch cards with instructions they used to stick into computers before keyboards were invented.

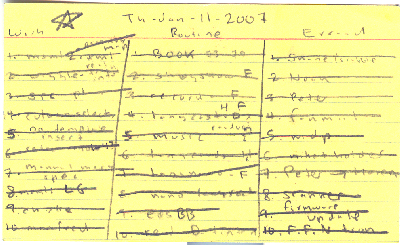

It works like this: the orders go on the lined side, one per line (more or less). The front of the card, the lined side, is binding; I have to do this stuff, I can't erase it. On the unlined back of the card, I can write free form stuff, notes which I don't have to obey, but don't want to forget. At the top of each card goes the date. Then I divide each card into three columns: work, routine, and errand. Work is pretty self-explanatory. Routine is stuff that I expect to do every day, like shovelglove. I'm big on routine, so this column is always full for me. Errand is one-off stuff like shopping or calling a friend or paying a bill. Almost every task I can think of obviously falls into one of these columns, and it's a good way to balance, at a glance, three fundamental priorities that most of us have. You can think of the columns as roughly corresponding to people as well. Work is your boss and coworkers. Routine is yourself. Errand is your family and friends. If, on average, the columns have roughly the same number of rows, you're probably achieving a good balance. If not, you may want to take steps to see that they do.

| front (binding orders) | back (non-binding notes) | |

|

|

The fact that lined index cards have 10 rows is helpful too. It's a built in sanity check on your ambition: much as you may want to do more than 10 things in each column, it's probably not very realistic. That limited space forces you to be realistic and make considered, deliberate trade offs that you choose, rather than just waking up to the fact that life imposed certain tradeoffs on you after a while. On weekends and holidays, I don't bother breaking it up into columns. I just do a single column-wrapping list. I thought at first that I'd take weekends off from todo-ing, but discovered that I actually enjoy it to much to do without it - I'm just careful not to be too ambitious.

Cross out what you've done as you do it, and then at the end of the day make a star on the card if you've done everything (it's amazing how motivating silly things like stars can be). If you didn't get everything done, there's no make up the next day. File it and forget about it, move onto the next daily card. You can copy undone tasks onto the new card if you still think they're worth doing. It's a tad unsatisfying to file a card with uncrossed out items, and to copy them over, and that's precisely what makes this system such a powerful tool: it forces you to get good at budgeting how much you can get done by giving you quick and jarring feedback on how good your budgeting was every day. But at the same time, it's liberating, because every day is a new start; you're not carrying around an enormous list of undone todos with you. This also has the advantage that you can never lose more than a day's worth of todos at a time, as you could if you kept them in a notebook you carried around with you. You have (if you file the cards) a record, but it's not a record you have to carry around with you and be conscious of every minute.

It might seem a little strange in this day and age, especially for a computer programmer like myself, to use a physical, paper based task management system instead of an electronic one. But there are two significant benefits:

1) physical things seem (and probably are) more permanent. They are harder to change or destroy without leaving some kind of evidence. They radiate a greater authority.

2) electronic systems constantly tempt one to spend increasing amounts of time diddling with the system itself. Nothing is more destructive of productivity than an excessively powerful and overcomplicated productivity system.

Note: listen to (or read) more about Personal Punch Cards in the podcast episode in which they were originally described.

2. Officer: Monthly Planning with Monthly Resolutions

A month is a much better granularity than the more typical yearly resolution we make on new years, because you can estimate better on that smaller scale, and recover and reset faster. And it's long enough (over 21 days!) for some habituation to occur, even with a slip up or two.

I write my monthly resolutions on red index cards and file them in the same box as my yellow daily footsoldiers. If I accomplish the goal, I give it a star. As an additional reminder, I've also been noting my current resolution on my "big picture," described below.

Note: listen to (or read) more about Monthly Resolutions in the podcast episode in which they were originally described.

3. General: Lifetime Planning with The Bigger Picture

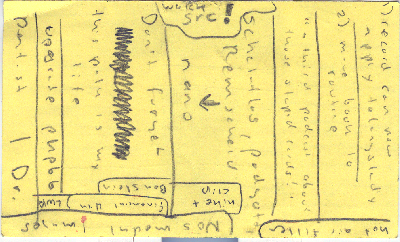

I started out using index cards for the chain of self-command "general" as well, but found that it wasn't quite satisfactory. So now, instead of using 3x5 index cards, I use an 8x11 sheet of paper. I call this the Bigger Picture. Seems like a superficial (and perhaps suspiciously cute) change, but it's actually quite profound.

Here was the problem I was having: Right from the get-go, the daily cards have been fantastic in terms of getting myself to do a lot every day. Using them, I'd gotten the micro level of task management down pat. The monthly cards have also been great at their job of keeping me focused on one medium sized goal at a time. And in terms of more free from stuff, random unformatted ideas, I've been capturing this stuff very effectively for years with my audiodidact system of carrying around a voice recorder and babbling into whenever something occurs to me. Still, I wasn't capturing everything. Some important tasks, issues that were really nagging at me, were still getting past these nets, mostly bigger picture strategic stuff, stuff that was too big for a daily task, too amorphous for a monthly task, and too interconnected with other issues, so that it just got lost in my audiodidact stream of consciousness. The yearly index cards, that were meant for the purpose of capturing this kind of concern, just weren't doing the job. They were sitting at home in a box, and I never really looked at or updated them. They were armchair generals. I needed a commander in the field.

My whole big picture life strategy has to fit on one 8x11 sheet of paper. Just as having a small 3x5 limit of a day is helpful in filtering out extraneous tasks on an index card, the 8x11 limit, gives me an effective (but somewhat more accommodating) limit for life scale issues. It's more room than a day, but not so much room that I don't have to make decisions about what just isn't important enough to make the cut. I've come to the conclusion that if you can't condense your goals to one 8x11 page, you probably can't achieve them. You'll probably never even be sure what they are.

For the daily index cards, it's no big deal if I lose one. It's just one day's work, and frankly, if I lose it that day I can probably remember most of it, and if I lose it after, it just isn't that important. It's out of scope, to speak like a programmer. But the big picture stays relevant over time, and there's a lot more information on it. So it's very helpful that there is an electronic version that I can backup (I used ms-word but any word processor will do). I update mine once a week in electronic form, then print it out, fold it up, and carry it around with me in my wallet. I'll scribble amendments on it during the week, and update the new version next Monday morning. This gives the benefits of having something low tech and tangible, with the power to easily backup and refine a complex document that computers give me.

Although the general is the highest rank, in contrast to the daily and monthly cards, nothing I write down here is binding. It's all merely advisory. To use David Allen's terminology, it's primarily about getting "open loops" out of my head and onto paper (and officially excorcising the loops that don't fit).

Note: listen to (or read) more about the Bigger Picture in the podcast episode in which it was originally described.

Auxiliary Systems

I have a few more systems/concepts that don't fit directly into the "Chain of Self-Command" but complement them nicely. You can think of them as irregular, auxialiary forces in your army of one.

Compound and Atomic Tasking

When you write down a task on your daily todo list, should you try to break it up into as many atomic subtasks as possible, or should you try to glue together several related subtasks into a single compound supertask?

The answer is, of course, that it depends. And what it depends on most, I think, is whether the task in question is something routine, that you do every day, or a one-off, a novel or unique task. Routines should be compound, one-offs should be atomic.

Routines, stuff you do or want to do every day, tend to be things you understand well. You know how long they will take. They are not surprising. You understand the associations between routine tasks, if they exist. So it makes sense to stick them together if you can, because then instead of having to remember or write down five things, you can get away with only having to remember or write down one. It also puts some extra pressure on you to do some of the important but seemingly optional stuff along with the basic necessities. Most of us wouldn't leave the house without showering (I hope). But far too many of us leave the house without exercising. If you bundle exercise and shower, the exercise becomes non-optional. All of a sudden you can't leave the house without exercising. This is a really simple, but really powerful motivator. And it's very natural. The association already exists, you're just formalizing and strengthening it. You can also think of it as associative tasking.

The danger with compound tasks is that you will overwhelm yourself with monstrously hard quadruple-decker tasks. That's why I only recommend it for routine tasks that you understand very well and have some natural association. You know how long they're going to take, and you know how they fit together. For one off or novel tasks that you don't really know how long they'll take, I recommend the opposite: break them up into as many small parts as possible.

Novel tasks almost always take longer than you think. By breaking them up into tiny parts, you factor this extra time into your plans (because each part takes a row away from other potential todos). You're less likely to overextend yourself. Some one-off tasks, like sending an email to someone, might be easier to judge, but it still makes sense to keep them nice and atomic because it doesn't have any natural associations with other tasks that will help you bundle it. Plus if you segregate your routine and one off tasks, as I do with my personal punch cards, filling up a row with a little task helps compensate for the inevitable other row that is going to take much longer than you think. And you want to fill these rows with as many easy, well understood things as will fit, both to keep hard poorly understood things from sneaking in and overwhelming you, and to give you a motivating sense of progress as you cross these things off. I've found that there is nothing like a sense of progress, even a somewhat artificial sense of progress, to motivate me to get more done.

Retroactive Tasking

The sense of progress is so important, that if I do something task-worthy that I want to give myself credit for, but neglected to add to my todo list in advance, I'll retroactively add it (and immediately cross it out). Such retroactive tasks don't absolve me of the obligation to perform any of the other tasks to which I've already committed, but giving myself credit for having accomplished them makes me feel (and so be) that much more productive. And if you look at your todo list as a record of accomplishments as well as a plan, it's a matter of simple accuracy to make a note of opportunistic achievements as well. By this kind of positive reinforcement, you'll train yourself to be in a mode of constaintly looking for such low hanging productivity fruit. You become the kind of person who automatically cleans up easy messes.

Audiodidact & Autotherapy

There are two components to audiodidact: input and output. Input is very simple: I listen to a ton of audiobooks. Output is where it gets more interesting. Among other things, I carry around a digital voice recorder with me on my urban ranger walks to record todos, random ideas that pop into my head, and keep a kind of audio diary. It's very therapeutic. Autotherapeutic. Kind of like having your own shrink, except without the hundred and fifty dollar an hour charge.

I was an English lit major and trained to be a librarian. Now I sit all day in front of a computer writing code. When I come home, there are a thousand practicalities to attend to: dishes, vacuuming, laundry, etc. I miss reading, and dread the dull chores that now take up my free time instead. The solution? Audiobooks. I know a lot of people who listen to books on tape during long commutes, and if I drove much, I'd do this, too. But where books on tape really shine for me is in these little nooks and crannies of time when I am doing some mind numbing chore. Not only do I get more "reading" done than I ever did before, but formerly dreaded chores become positively pleasurable.

As for Audiodidact output, it's basically what it sounds like: you talk into a voice recorder. How is this didactic? Well, it's as deeply auto didactic as you can get. By talking, you follow the Socratic injunction to know thyself.

It works like this: I carry around a recorder with me an mumble into it for a few seconds whenever I get a bright idea or want to blow off steam. Until recently, people would have thought I was crazy walking down the street talking to myself, but now with cell phones it seems perfectly normal.

Once a week or so, I listen to the week's recordings and transcribe them. The transcription is a tad time consuming, but it's not too bad, once you get a sense as to how loquacious you should be, and it's fantastic for your typing skills. Most importantly, it forces you to review what you said, at least once, which is good in terms of this being a meaningful exercise in self-knowledge.

Habit Calendar

Most everyday systems consist of simple rules for how to behave. Every day, either you abide by the rules or you don't; or there's a third possibility, you could be exempt (because it's an S day). So you take a calendar and make a green mark on every day you succeed, a red mark on every day you fail, and a yellow mark for every S day. Green, yellow, red-- like a traffic light. It's not a whole lot of effort keep track of this; there's just one data point per day, and at the end of the month you'll have a very striking picture-- literally, a picture-- of how well you adhered to the behavior you set out to achieve.

You can tie this directly into the "chain of self command" by tracking your daily footsoldier compliance. Days you get all your tasks done, that you've "starred," also get a green tick in your habit calendar. Days you don't get red. Doing this has upped my compliance pretty remarkably.

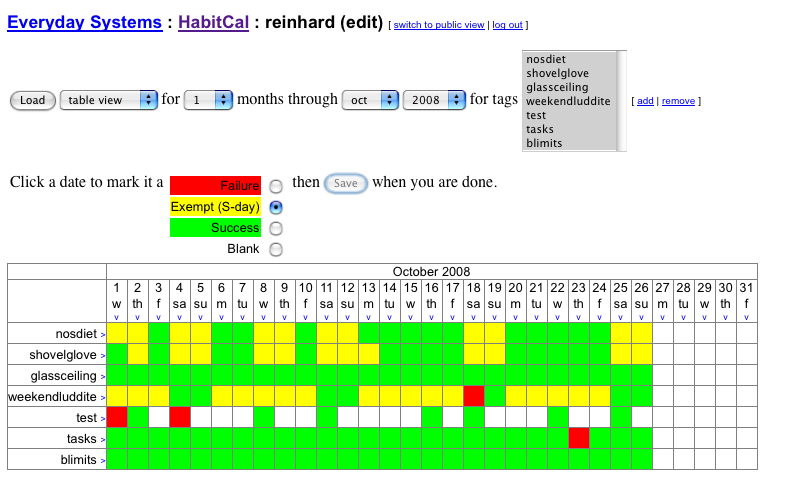

A paper calendar works fine if you're just tracking a single habit, but I've created a free, online HabitCal that makes it easy to track several at a time, generate statistics, etc. Here's a screenshot of the habitcal in table mode (there are a bunch more).

Personal Olympics

If 3 classes of Olympic medals can spur on athletes to almost superhuman achievements, maybe a similar tiered incentive scheme can be applied to mundaner stuff -- like your exercise routine, or losing weight. There are no actual medals involved, just different levels of patting oneself on the back. The psychology behind it is sort of like the little stars they give kids in elementary school, those little worthless but highly motivating stickers. The idea is that somewhere, deep down inside, despite knowing better, we still respond to that kind of thing. The world-class Olympic connotations take something we might think of as very personal and pathetic and make it seem worth our attention. Yes, it's a trifle absurd, and I'm not sure this will work without a bit of a sense of humor, but you know, you really should be taking these personal problems seriously, and if putting them on a world stage is what it takes, that's less absurd than just being quietly defeated by them.

Distraction Management

The techniques above focus on positive productivity -- or at least, properly channeling productive impulses. What about negative, unproductive impulses like procrastination? I have a bunch of systems to address this side of the problem as well.